Does your family rally around a specific professional sport? Our family has hung their dreams on baseball. We played it. We watched it. We love it.

My heart has loved the Astros the longest. Jeff Bagwell, Craig Biggio, Kevin Bass, Nolan Ryan, and Jose Cruuuuuuuz are just a few of the players I watched. My mom taught the children of Terry Puhl, and I earned some extra money babysitting for them. When a pro player called the Puhl house (no cell phones then), this teenager stammered as my heart felt it would beat out of my chest. I did everything I could to sound unfazed when answering and relaying messages. I’m sure I was unsuccessful.

When our family moved to Kansas City, my favorite players’ names changed, but the love for baseball remained just as strong. So why did it take so long for me to visit the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum? I’m ashamed to admit I have no good excuse.

Venturing solo, I decided to give the museum a try. Ordering tickets online would have been easy, but my friend Sarah had a free pass. Free is my favorite four letter word, and I realized I couldn’t delay my visit any longer.

The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum sits at 18th and Vine in Kansas City and shares space with the American Jazz Museum. Outside construction hinders the traffic around the museum, but parking behind the building is not only easy; it is also free. Love that word!

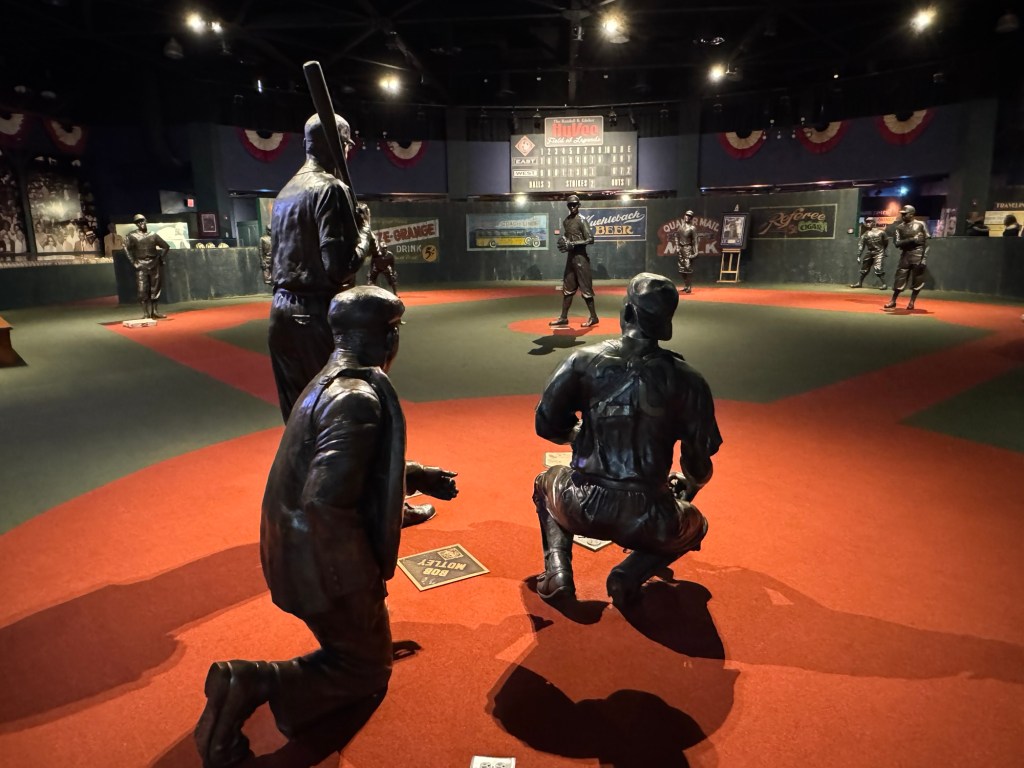

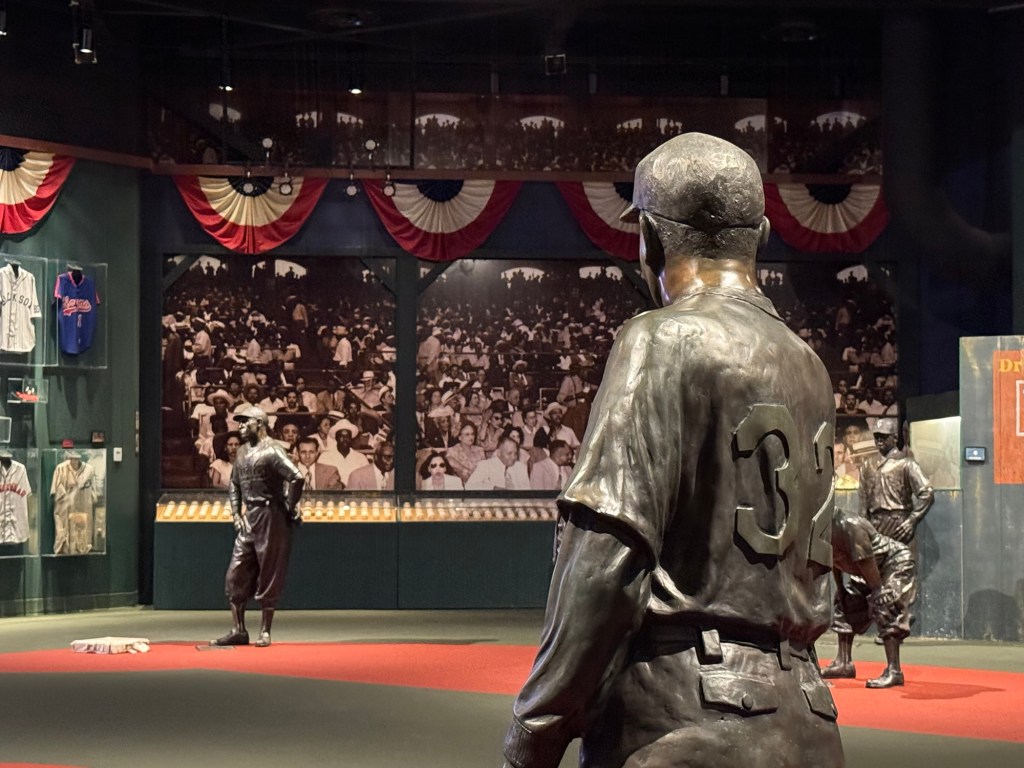

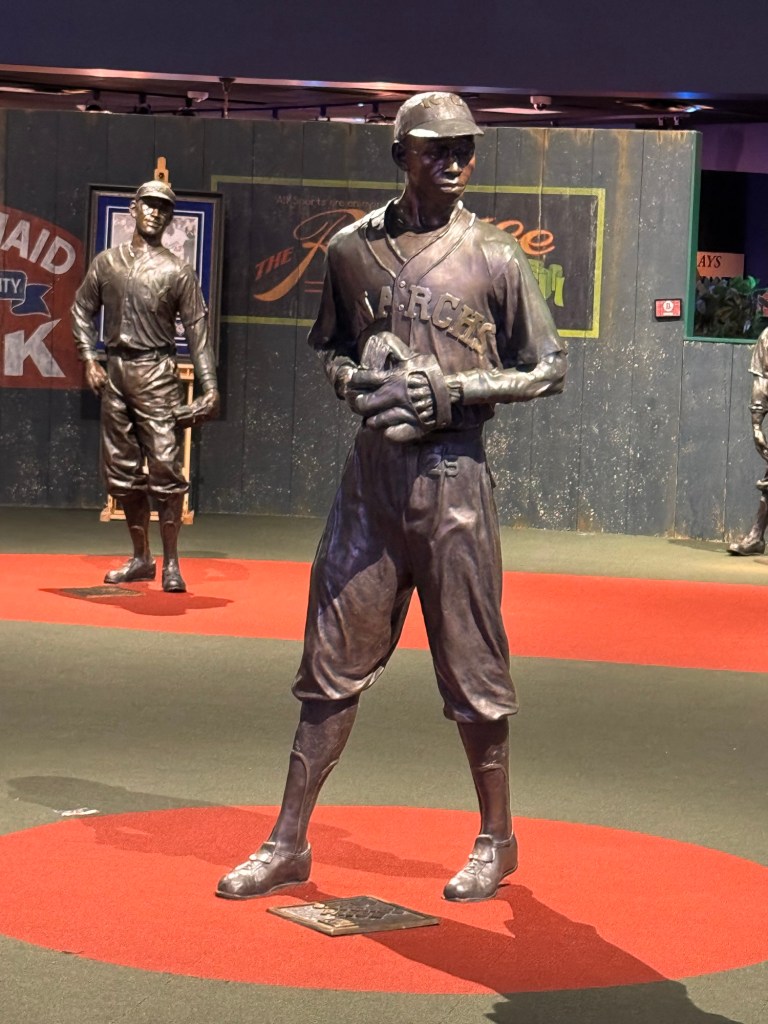

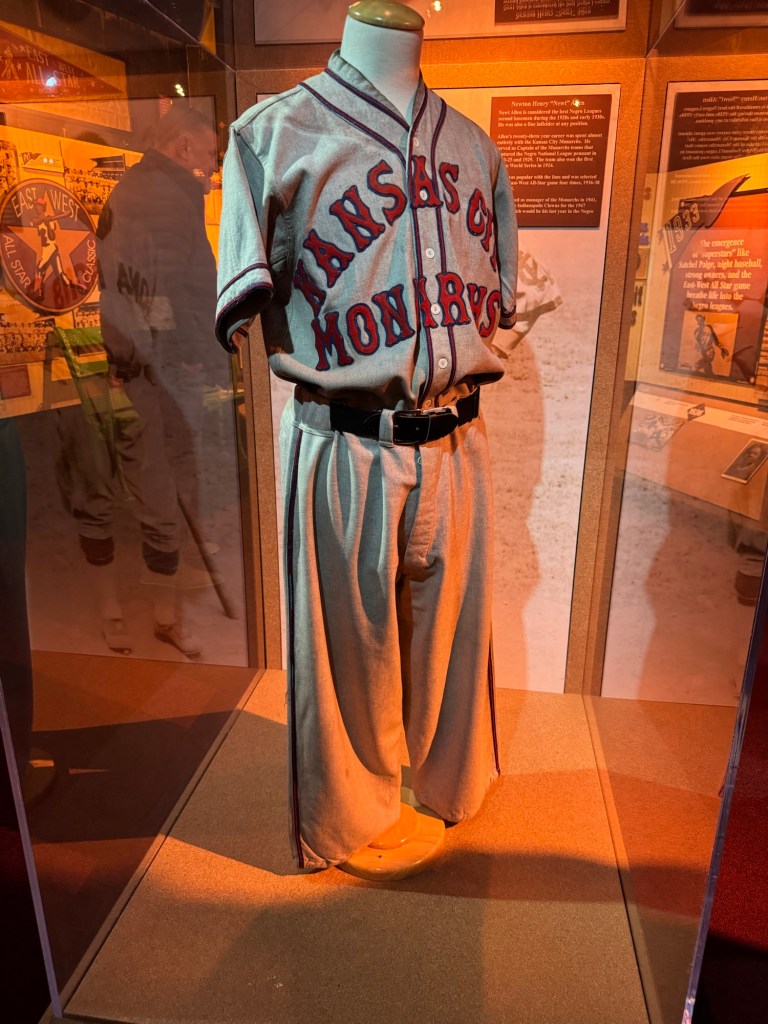

Minimal security makes entry easy. As you walk in, a creative baseball bat and three base seat sets the tone. Videos play and timelines are displayed, but the anchor piece of the museum engages you with the negro players of the past standing on the field ready to play.

The first black on-field coach in Major League Baseball, Buck O’Neil, stands with you as you look onto the field from behind home plate. Satchel Paige readies himself for the first pitch to Josh Gibson as Cool Papa Bell awaits a fly ball in the outfield. The statues draw you in as history begins to roll back and the experience takes over.

As you wind your way through the timeline of negro baseball, James Earl Jones’s voice wafts out of the theater, and different stops provide a new perspective of the ever-present baseball game.

How do you make an actual baseball? Well, not much has changed since baseballs first came off the production line. The size has remained unchanged since 1876. Its interior became set in 1911, and cowhide replaced horsehide in 1974. There are plenty of videos on YouTube showing how every red stitch is sewn into the ball.

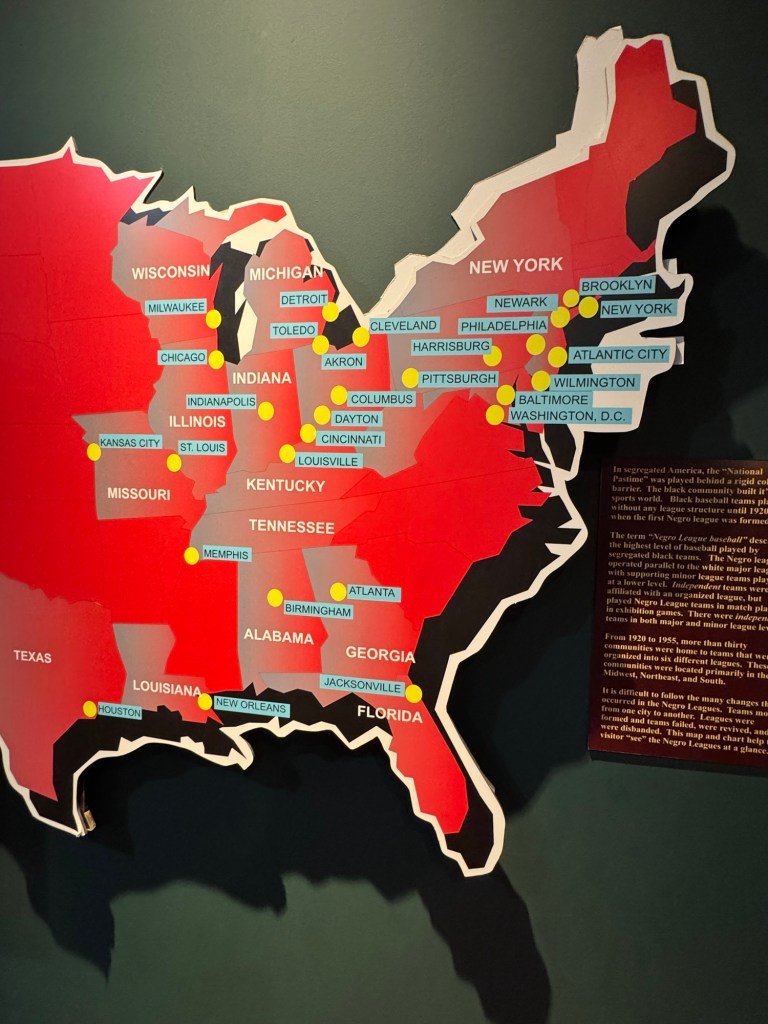

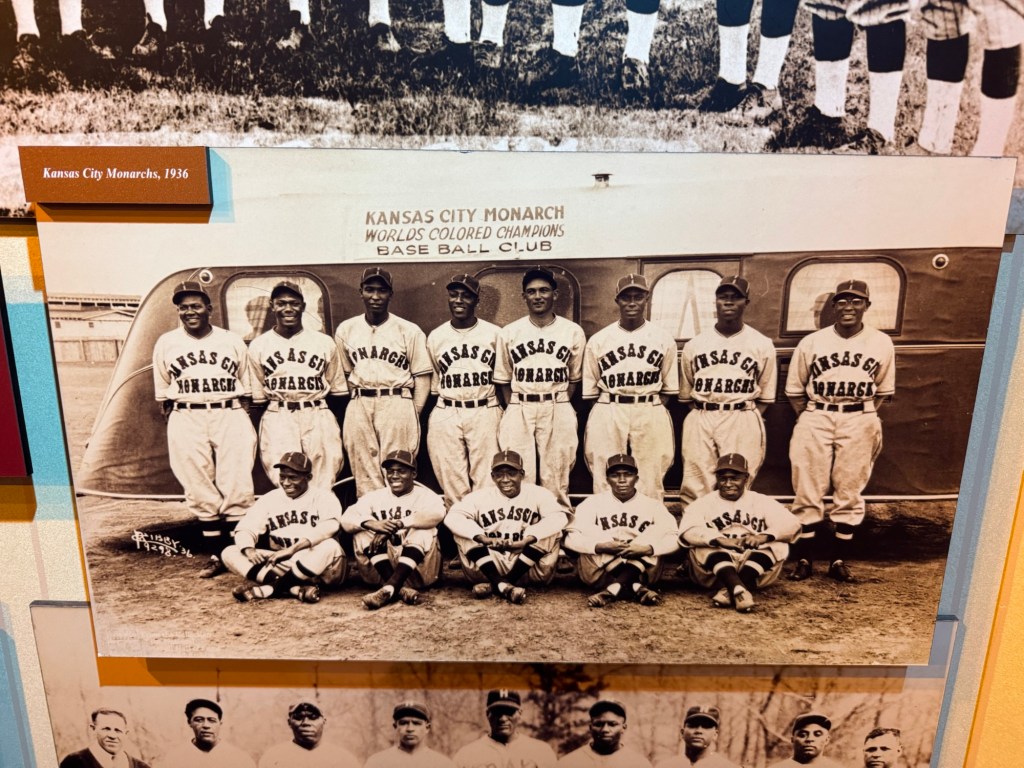

The Negro Leagues had many struggles along the way. Funding was often at the forefront. Loose organizations formed for a time, but it wasn’t until 1920 when Andrew “Rube” Foster met with negro team owners in the YMCA (just around the corner from the museum) to form the first successful Negro Leagues.

When did night baseball begin? Well, a man named J.L. Wilkinson created a portable lighting system that began the era of night baseball. Trucks towed the lights to different locations and allowed working people to go and enjoy the game. The museum states the first Kansas City Monarchs night game occurred on April 28, 1930 and prepared the way for MLB to introduce night ball. It was five years before MLB implemented a lighting system.

The United States struggled to give freedoms to black players and teams. Despite many negro games outselling their Major League counterparts, negro players found inequalities within the game as well. Many white owners took over teams, and some negro players moved to Hispanic teams. Not only were they given star treatment while playing abroad, but their salaries increased.

Other fun activities occurred during the Negro League’s successful run. Clown ball came to the games. Think Harlem Globetrotters. Place those players on the baseball field, and you have clown ball. In fact, the choreographer for the Harlem Globetrotters, Goose Tatum, was also planning skits for the baseball team. Many people loved to see the spectacular moves while others felt the style of play fed the theories of black stereotypes. Surprisingly, Hank Aaron was once a clown ball player before his time in the majors.

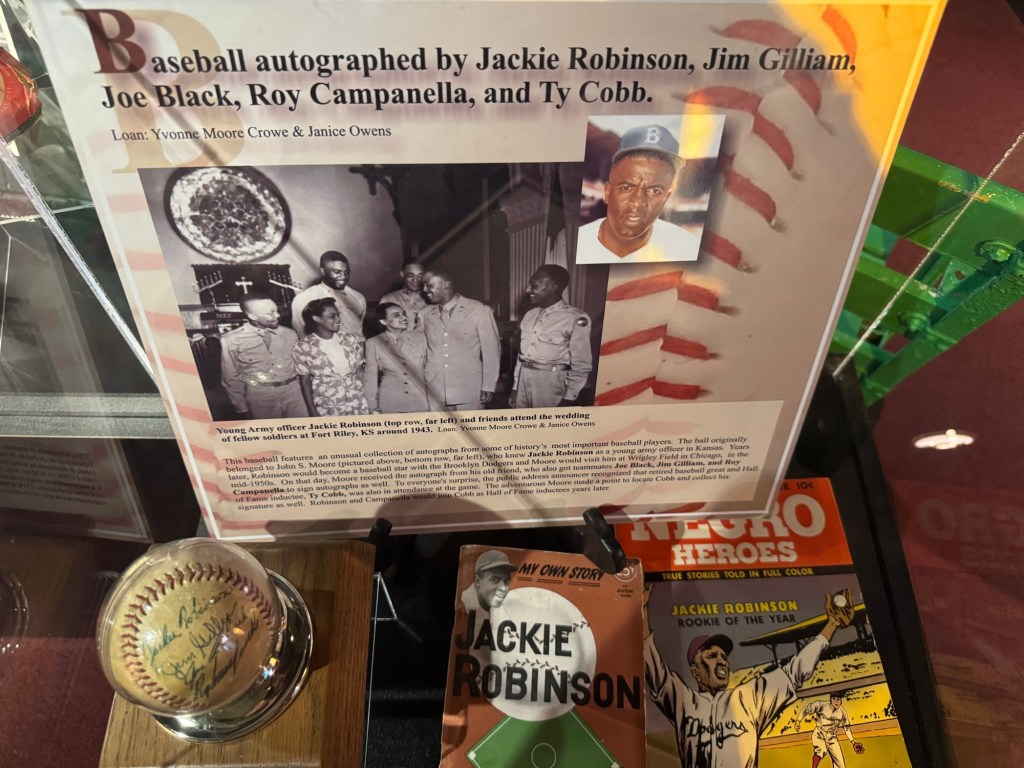

Eventually Jackie Robinson stepped on the field for a major league game. His steps led the way for other black players to enter the majors. As awesome and amazing as that was for humankind, it marked the beginning of the dissolution of the Negro Leagues. Quality players left for more money, and one league—the Major Leagues—became the future.

I am so thankful for the hard work hundreds of people put into the game of baseball. To all those who were good enough to play in the majors but never could because of their race, I am deeply saddened.

The Negro Leagues Museum holds Golden Glove awards for many of those players. These were given to the players (some posthumously) and were made out of the exact materials as the ones the Major League gives out. These awards sit proudly in the museum. There is also a remarkable display of baseballs. Each one is signed by a player of the Negro Leagues.

And as you leave, you are invited to the field to stand in the midst of those players who paved the way. They paved the way so you and I can enjoy a game where athletes of every race are invited to compete together…and the world is better for it.

Leave a comment